“We are powerful.”

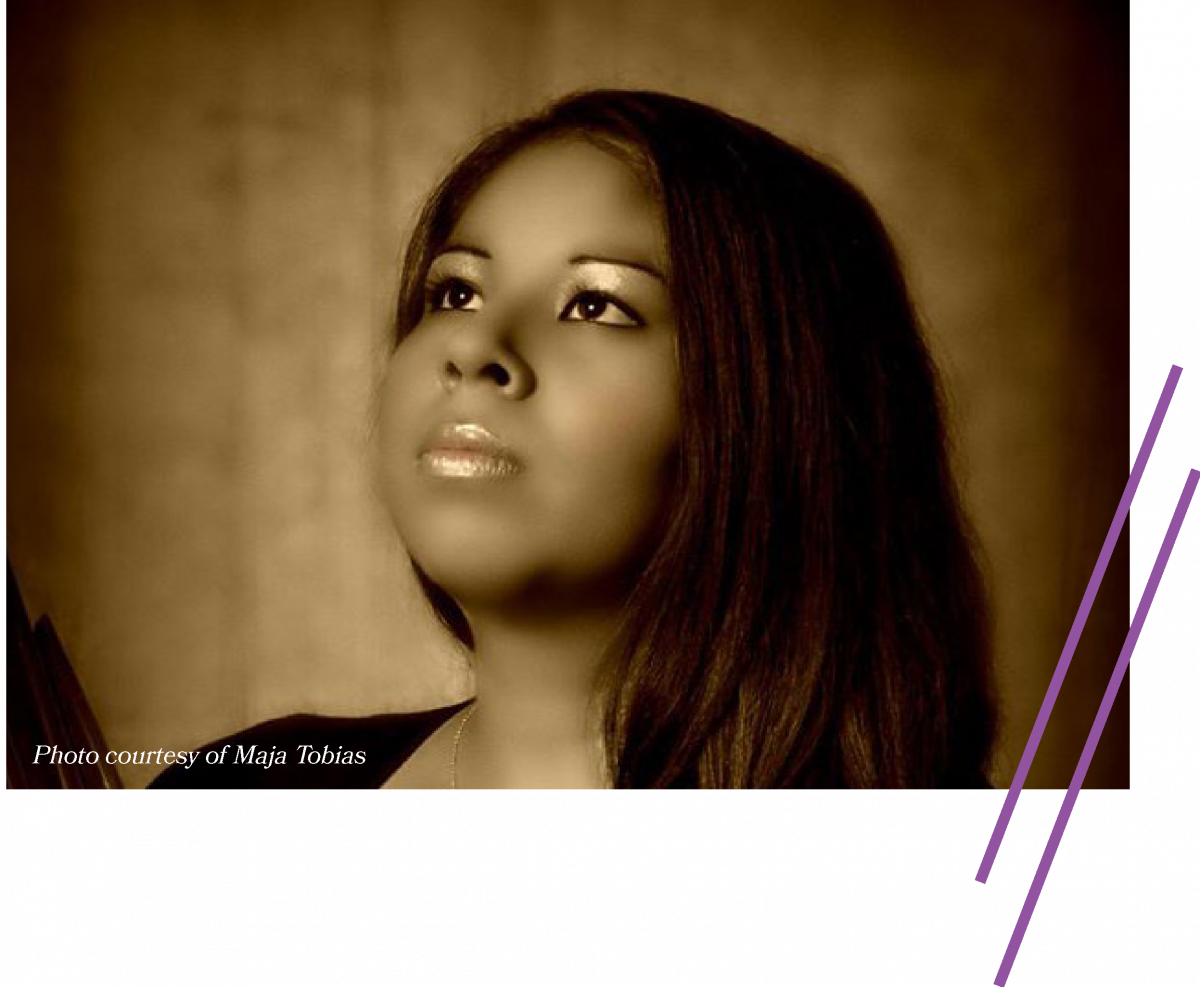

Alumni highlights: Trisha Etringer

As the Dakota Access Pipeline protests turned violent on Labor Day Weekend in 2016, Trisha Etringer, ‘19, was on the frontlines, two months pregnant with her daughter.

Faced with the barking dogs of private security guards, Etringer stood up for the rights of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and was pepper sprayed for her efforts.

It was a moment that would define her life, a moment when Etringer, a member of the Winnebago tribe, decided that tackling the issues which plague indigenous communities would become a career.

“There I was, an Indigenous person standing for Indigenous people and their land rights, and this is the direct answer we get,” said Etringer, who graduated UNI with a degree in psychology. “So, after that, I thought ‘this is my life’s work now.’ I want to fight for Indigenous rights and be at the table having those conversations so people know that we’re still here and they need to hear from us.”

The journey both to and from this moment wasn’t easy. The mother of four now works for the Great Plains Action Society, advocating for Indigenous rights across the Midwest, persevering through homelessness, intergenerational trauma and domestic abuse to get there. She almost dropped out of college twice, but successfully graduated thanks to critical assistance from UNI faculty and staff. And through it all, she discovered the joys of her heritage.

Before she could help anyone, she had to discover herself.

Etringer was raised in a white, suburban neighborhood with her adopted family, her aunt and uncle, and attended Catholic school. Her adopted father earned a steady income working as an electrician for John Deere. Her Indigenous heritage was not a part of her life. For the most part, Etringer was not even aware she was different from her white classmates.

That started to change when she met the other side of her biological family, members of the Winnebago tribe who lived in Sioux City, at the age of 12. By the time she was 15, she was plagued with questions of her identity and facing troubles at home, so moved to Sioux City to live with her older sister, Jessica.

“That’s when I really began my journey of knowing who I was and where I came from,” Etringer said.

Jessica taught her the ways of the Winnebago tribe, the meanings of their songs and the importance of the Pow-Wow. She also learned about the impacts of the intergenerational trauma of Indigenous people stemming from the erosion of their culture.

“They got their language stripped away from them,” Etringer said. “Their hair, their clothing, their parents, their children, all stripped away.”

When she was 21, Etringer had her first child, Javon. In 2015, motivated to do something more with her life, she decided to attend UNI to study social work and set a good example for her children. She was 27 years old and a single mother when she enrolled.

“I had no idea what kind of journey it would be,” Etringer said. “And it turned out to be one of the most powerful journeys I’ve ever taken.”

At UNI, the gravity of her heritage and her upbringing became apparent when she learned about white privilege for the first time during a lesson in the classroom of social work instructor Belinda Creighton-Smith.

“I broke down into tears, because I was like, ‘how could I not see this?’” Etringer said. “I grew up in a white privileged home. I was immersed in that, and I didn’t realize there were people, my people, living in Sioux City who were homeless and struggling and in poverty. Now it was my turn to go back and correct these social injustices.”

And while her experience at UNI yielded profound moments of self discovery, it was not without challenges. She was homeless for a time and struggled through a relationship fraught with domestic violence that caused her to almost drop out of school twice. But both times, UNI helped pick her back up.

“When I was facing homelessness, UNI came in and basically saved me,” Etringer said. “They put me in a single-parent dorm so I could still go to class.

“We toughed it out,” she continued. “But at the end of the day, I chose to go to UNI because I wanted my son and daughters to see that they can do this. You just have to put your mind to it, and to see their mom graduate and walk the stage — that was something I wanted them to witness.”

But she might not have made it without the intervention of Jan Cornelius, a secretary in the psychology department. It was Cornelius who witnessed Etringer come into the office in tears, overwhelmed with the burden of domestic abuse, ready to hand in her papers to drop out.

“She looked me in the eye and said ‘I want you to go to counseling. And then, if you feel the same way that you do after you talk to the counselor, then come talk to me, and I’ll sign this for you,’” Etringer said.

And she did just that, and found a path to stay in school. When she graduated, she sought out Cornelius to thank her. The two teared up sharing the memory and embraced. “Trisha is an extraordinary person,” Cornelius said. “I’m just thankful I was there when she needed someone.”

After graduating in 2019, Trisha moved back to Sioux City to work as the director of operations for the Great Plains Action Society, a collective of indigenous organizers of the Great Plains working to resist and indigenize colonial institutions, ideologies and behaviors.

Specifically, Etringer’s goal is to work within indigenous communities who suffer from high rates of suicide, alcoholism, depression and historical trauma. “We can’t let this go on any longer. We need to help these people heal themselves,” she said.

Etringer is exploring a partnership with Rosecrance Jackson Center, an addiction recovery center in Sioux City to combat these issues. Beyond that, she has helped lead the Native COVID-19 Rapid Response Team. The virus was particularly rampant in the Sioux City-area indigenous communities, where many work at the meatpacking plants that dominate the local industry or are susceptible to infection due to high rates of homelessness and alcoholism.

Etringer also sits on the Native American Advisory Board for the Sioux City Department of Corrections along with other Indigenous leaders, with the goal of improving the relationship between the Native community and the Department of Corrections, and sits on the board of the Urban Native Center, which serves the local Indigenous population.

She has also returned to her alma mater, working on a land acknowledgment project and mural with Bettina Fabos, a UNI professor of communications and media, and Angela Waseskuk, a UNI instructor of art. Etringer will present decolonization workshops for UNI faculty about how they can change their syllabi to include the Indigenous perspective.

And as Etringer begins the next journey in her life, she looks to the future of indigenous people to see not a disappearing culture repressed by the grindstone of colonization, but a thriving, powerful part of society motivated to validate the sacrifices of their ancestors.

“My ancestors went through really hard times, and I am the product of their survival,” Etringer said. “So I have to pay that forward. My kids need to realize that this is not always a sad story."